The medieval castle of Kefalos and the monastery of Agios Antonios in Marpissa, Paros

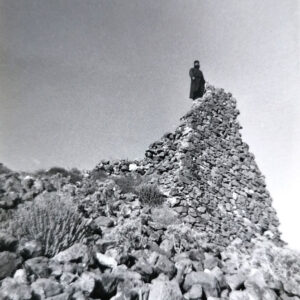

The hill of Kefalos

The hill of Kefalos in eastern Paros, which according to Dimitrios Paschalis is a distinct coastal mountain, is one of the most visited sites of the island. Its geometric shape, the ruins of the medieval castle opposite Antikefalos hill, the monastery of Agios Antonios dating from the 16th century at its summit, the beach of Molos at the foot of the two hills, and the view of SE Paros and the sea compose a landscape of exceptional natural beauty and particular historical interest.

Kefalos, the hill’s name, which was later extended to include the lower villages of the area, is of pre-Hellenic origin. Kefalos was the son of Hermes or Pandion, a hero whose name was given to both the municipality of Kefali in Attica and Kefalonia (Cephalonia). Moreover, there are capes which bear his name on several Aegean islands, such as Imvros, Skiathos, and Kythnos, and elsewhere. An earlier reference to the name has also been found in a sigillum of 1593 by Patriarch Jeremiah II, in 17th century inscriptions, in texts by C. Buondelmonti and J. P de Tournefort (18th century), as well as in travel books by D. Tagias, Marco Boschini, V. Coronelli, C. Gouffier, L. Ross, C. Hopf, and others. According to Parian literary scholar Ioannis Protodikos, Kefalos derives its name from the homonymous fish.

One can access the monastery via two paths from either Marpissa or Marmara. There is also a paved road from Marpissa. Whether on foot or by car, the visitor will find the ascent a special and worthwhile experience.

At the top of the hill, which rises 229 meters above sea level, in addition to the stunning views and the picturesque 16th century monastery, the visitor can walk among the ruins of churches, fortifications, cisterns, and houses dating from the period of Venetian rule, between the 13th and 16th century. During the Venetian period, the residence of the ruler or lord of the island occupied the site where the monastery is located today.

On the hill of Kefalos, in the monastery and the ruins of the castle, there are built-in or scattered marble architectural and sculptural members of ancient buildings (archaic capitals with columns, carved tombstones, and others). It is believed that their presence at the top of the hill indicates the existence of a pre-Christian building -or even buildings. When these were destroyed, probably in post-Byzantine times, the church of Agios Antonios was built using their materials.

In descriptions of 1584, it is mentioned that Paros has one “chora” (capital, large settlement), namely Parikia, and two castles (fortified settlements), namely Kefalos and Agosta. William Miller also mentions Venetian castles; paraphrasing him, the strongest one was the castle of Kefalos, which Nicolo Sommaripa built circa 1500 as his seat, on a steep hill above the sea.

It has been well established that when the Venetians occupied Paros in 1260, they fortified Parikia, building the castle as the ruler’s residence and the administrative seat of the island.

The castle of Naoussa was built in the late 13th to early 14th century, along with the characteristic circular tower which was added to the entrance of the port.

The castle of Kefalos has structural and other similarities with other Aegean castles built during Venetian occupation. Given the size of its area and the layout of the ruins, 1,000 to 1,500 people could have inhabited this site during times of peace or war. The exact date of its construction has not been established.

When Florentine priest C. Buondelmonti visited Paros circa 1415-1420, this stronghold already existed. He reported that the castle was located on a steep hill. Its existence has been confirmed as early as the beginning of the 15th century, as there is an inscription above the door of the church of the Annunciation. This inscription commemorates the names of the church founders and 1410 as the year of its establishment.

According to Athanasios Vionis, professor of Byzantine archaeology and art at the University of Cyprus, the first construction phase of the castle fortifications may have occurred in the late 13th century. The outer defensive wall must have been built in the late 14th century by Niccolo Sommaripa, who moved the seat of administration from the castle of Parikia to that of Kefalos. Archaeological findings (surface ceramics) indicate that the site was continuously inhabited from the late 14th to the early 16th century. The castle was besieged and eventually captured by H. Barbarossa in 1537.

Regarding the last epic page of Venetian occupation, William Miller wrote that, having effortlessly captured the smaller islands, Barbarossa arrived in Paros and ordered its surrender. Bernardo Sagredo, baron of the island, determined not to succumb, left the castle of Agousa (Naoussa) to the enemy, and barricaded himself -along with the small force that he ruled- in the fortress of Kefalos; there, he not only resisted for several days, but he also carried out effective exits to attack the besiegers. Nevertheless, a lack of gunpowder forced him to surrender. Cecilia Venier, his wife, was allowed to return to Venice, and Sagredo was later released by a sailor from Raguza who had previously served as a rower in one of his galleys. The Parians, approximately 6,000 in number, were slaughtered or neutralised. Despite Sagredo’s attempt to regain his lost island by offering to pay tax to the Sultan, the treaty of 1540 placed Paros under Ottoman rule.

Andreas Kornaros reports that, in order to besiege the castle, Barbarossa transferred the cannons from his ships onto land. Following its capture and destruction, Kefalos was deserted and has not been inhabited since.

Nowadays, only ruins of the castle have been preserved, and are scattered throughout the area around the top of the hill. The castle consisted of two parts and was protected by an inner and an outer defensive wall. The ruins, piles of stones of its inner and outer walls, divide the site into two levels. The catholic cathedral church and the residence of the lord with the necessary auxiliary structures were built at the highest level. There were also rows of one-room houses, built against the outer wall.

Regarding the wide variety of buildings on Kefalos hill, Professor Manolis Sergis comments that: the hill of Kefalos is a typical example of “constant cultural continuity” or “overlapping cultural layers”, both of which are phrases that we use to describe our island. There are ancient buildings, Roman, medieval, Frankish, all pagan; and on top of them, the purifying influence of Christian buildings. In a single area, we find layers of different cultures, which at times coexisted in peace and at times clashed violently …”

The walls

The outer walls, nowadays in ruins, enclosed and fortified the top of the hill, a total area of 35,000 square meters. According to Professor Athanasios Vionis, they appear to have been built in two phases, predating the construction of the current monastery of Agios Antonios.

The double enclosure had seven towers effectively protecting the defenders from raids. The ruins of the walls are preserved to this day (6 – 7 m high and 1.5 m in thickness). Both the inner and outer walls were reinforced with towers in the corners and built of roughly cut stones. According to Robert Sauget, the castle had eight cannons.

The chapels

Inside the castle courtyard, there are nine single-naved, vaulted churches, most of which are twin. Only one has been renovated and is dedicated to the Annunciation of the Virgin; according to its lintel, this church dates from 1410. The others are in ruins. Their dimensions are approximately 7×3.5 m. Architectural members of ancient buildings and coloured tufa stones of unknown origin were used in their construction. In some of the small temples there are traces of hagiographies, frescoes, and illegible inscriptions. In one of them, south of the current monastery, there are drawings of boats that resemble those found in a very old chapel in Afouklaki, Paros, and in another chapel in Amorgos, which are unique in the Aegean. Sailors’ habit of drawing and dedicating ships on church walls has been studied by Michail Goudas.

The water cisterns

Three cisterns that provided water to the castle of Kefalos have been identified among the ruins. The largest was located in the building complex of the lord’s residence at the top of the hill, possibly in the basement of a tower. The ruins of a second and smaller cistern were found southwest of the temple of the Annunciation. The third cistern is located next to the ruins of the south gate.

The monastery of Agios Antonios

The temple of Agios Antonios constitutes the church of the monastery by the same name that has a few cells and other auxiliary structures. It was built circa 1580 and today occupies the top of the hill. It has been renovated and has granted this hill its second name.

There is nearly no information regarding its early history. Professor Nikos C. Aliprantis, who has thoroughly studied late 16th century documents, reports that it owned a significant estate. Relevant records in the General Archives of the State, from the 17th to the 19th century, indeed confirm this, as there are records of transactions between the monastery and property owners, both laymen and clergymen.

Initially, it functioned rather as an idiorrhythmic monastery. It later became cenobitic. In 1644, it is mentioned in a sigillum by Parthenios, Patriarch of Constantinople, and declared as the “patriarchal and free Stavropegial monastery of Agios Antonios”.

The monastery was protected and funded by money and donations from the family of Nikolaos Mavrogenis, ruler of Wallachia, who was originally from Marmara, Paros.

Agios Antonios belonged to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which was responsible for the proper management of its movable and immovable property.

According to a sigillum by Patriarch Gregory V, Agios Antonios was a birthplace of education and was liaised with the “Hellenic Education Centre” of Andros, thanks to the care and actions of the Mavrogenis family. Teachers were dispatched from Andros to Paros, on an agreed salary paid by the monastery, in order to teach grammar and other circular educational material to young natives and foreigners.

The monastery of Agios Antonios had accumulated a considerable amount of wealth. From 1819 to 1833, when the state took over school administrative expenses (teachers’ salaries, rent of buildings, etc.), it provided the national service of educating the island’s youth, by allocating funds to the school of Kefalos, as well as to the other schools of the island.

In 1893, in a memorandum by Ioannis K. Matsas, mayor of Paros, it is mentioned that Agios Antonios and its bequests (estates, lands, etc.) were dedicated to the church of Panagia Ekatontapyliani, which reaped the proceeds in order to beautify and maintain the Church and the Municipality…

During the Revolution, the issue of ownership of the monastery was raised by heroine Manto N. Mavrogenous and her relative Rallou Soutzou. In 1823, residents of the villages of Kefalos addressed the Minister of Religion to protest against Mrs. “Mado of Mavrogenis” with regard to the ownership status of the monastery.

Disputes over this matter continued until 1836, as indicated by the argumentation expressed in relevant documents written by lords, commissioners, clergymen, and other officials of the area’s villages.

In 1834, by royal decree, Agios Antonios ceased to exist as an organised monastery, as it had “no more than six monks”. From 1836 onwards, the monastery and its estate were owned by its respective tenants.

In 1840, the movable property of the monastery (church utensils, objects, and documents) came under the ownership of the State, as part of the central fund of the Ministry of Finance, as dictated by a protocol signed by Nikolaos Vatibellas, Mayor of Marpissa.

The church

The church is a cruciform inscribed church, with internal dimensions of 13×7.5 m. At its entrance, there is a marble lintel with a cross in a circle bearing the letters IC ΧC NIKA.

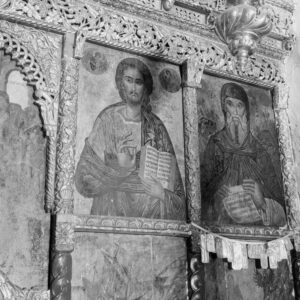

It has been hagiographed twice: first in the 16th century and then again in the 18th century. There are hagiographies of different eras, most of which have suffered significant damages. Today, only few specimens of the indoor decoration have been preserved, and the hagiographies that have worn out over time have been painted over “in a terrible manner” as Professor Orlandos characteristically states. The later hagiographies have a folk style and are similar to those of other temples in Paros. Two of the most characteristic agiographies date back to the 16th and 18th century respectively, both depicting a number of persons in representations of the Second Coming.

The marble pulpit rests on an inverted Ionic column, and its shields are decorated with six-winged cherubs and a carved cross. Reliefs and coats of arms adorn the founders’ graves on the floor. Important dates in the history of the monastery have been inscribed in various parts of the church.

The iconostasis, one of the most beautiful and best preserved in Paros, dates from the 17th century. It is wood-carved and gilded, with a height of 3 m and a width of 3.25 m. There are wood-carved plant-themed decorations on its edges, while in its centre rests the wood-carved gilded Cross. Its portable icons are Panagia Panachrantos (Virgin Mary), Christos Pantocrator (Christ), Agios Antonios, Agios Ioannis Theologos (Saint John the Evangelist), O Mystikos Deipnos (the Last Supper), Archangelos Michael, Agios Ioannis Prodromos (John the Baptist), and Agios Anthimos. There are additional icons on the shield of the iconostasis.

The ciborium, created in the 18th century, is gilded and in the shape of a rectangle. It has not been established whether the marble tabernacle belonged to this specific temple or to a pre-existing one.

The ecclesiastical books and other relics of the monastery are kept at the Ecclesiastical Museum of Marpissa.

… instead of an epilogue…

Nowadays, the visitor who climbs up the hill of Agios Antonios is filled with contradictory emotions. The ascent is an uplifting spiritual journey. Nevertheless, while wandering around the castle, through deserted piles of ruins, one cannot help but feel sadness at the sight of abandonment.

All of us hope and look forward to the restoration of the castle -even a partial one- that will give the visitor a clear picture of the past…

Konstantinos G. Rodopoulos

Sources

Aliprantis, N. C. (2017) The Holy Monastery of Agios Antonios in Marpissa, Paros, and the Castle of Kefalos: History – Art – Documents. Athens: Publication of the Historical Monastery of Agios Antonios in Marpissa, Paros

Vionis, Α.K. (2016) “The medieval castle of Kefalos in Paros”, Parola, issue 8, pp. 44-52. Available at issuu.com

Vionis, A.K. (2006) “The thirteenth-to-sixteenth-century Castro of Kephalos: a contribution to the archaeological study of medieval Paros and the Cyclades”, Annual of the British School at Athens. Vol. 101, pp. 459-492. Available at www.jstor.org