And all the houses celebrate, with the table set,

And with an eager heart accommodate the guest.

(Vassilia Kafourou – Asonitis, “Το Χωριό μου” / My Village)

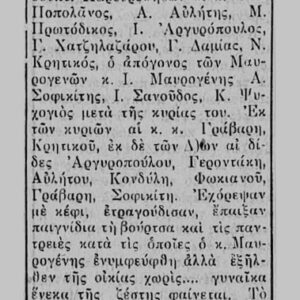

Feasts and celebrations are all about solidarity, camaraderie and love. Hospitable and sociable, the people of Paros share their daily life and the special events in their life with their fellow locals. Before the development of tourism, social relations between people were more cohesive. The people of Paros kept their houses open and welcomed everyone who called to wish them well on namedays or to participate in the joy of engagements, weddings, baptisms. Respectively, hosts soon would become guests, as they felt it their duty to call and wish well to those celebrating, for a treat and a dance.

K. Ragousi – Kontogiorgou (2004) mentions that the first to call was the priest, then men would call by noon and in the afternoon the women went to visit. According to spoken accounts however, visits were made from house to house by couples, men and women, in the afternoon and usually ended at the house of the “closest” relative or friend.

Preparations started days before, with the cleaning and whitening (limewashing) on the yards, terraces and walls of the houses. They carried water from the village wells in clay pitchers or tin containers, which they sometimes kept cool by dipping the bottles in baskets in the well or cistern of their house. There were three wells in the village, Bougados, Makronas and Tzipidos or Tz(s)ipidiotis.

Housewives kneaded bread and prepared sweet and savoury treats. They asked their guests “did you have wine or sweets earlier?” and served them accordingly. They offered spoon sweets, grape or sour cherry, traditional marzipan treats, home-made soft drinks (sour cherry, apricot) which they always kept in the cupboard, ypovrichio (vanilla fondant) with cool water from the pitcher and later from the ice refrigerator. “I would not dare to reject you, deny your offering and offend you…” was the usual answer to the treat.

Serving treats, by Zacharias Stellas:

They had a container, the “gkeses”, where they kept all clean teaspoons, the “gkesedohouliara” (the spoons of the cup). The host offering the treat (grape, quince, etc.) “took the tray before each guest” and each guest would take a gkesedohouliaro and “served themselves the sweet out of the setosoupa or sotokoupa (larger pot of the same set, containing the sweet)”. After they had it, they put the gkesedohouliaro in the nerosoupa (the other pot, containing water). Another woman, next to the host, immediately took it out of the water, wiped it with a clean towel and put it back in the bowl with clean spoons, for the next guest to use. This fashion (way) was particularly helpful in crowded occasions (baptisms, weddings, celebrations) as they only had very few gkesedohouliara to go round. (Stellas, 2004, pp. 135-136)

In the middle of the hall they set the square dining table, with the fancy tablecloth and cutlery. The treats were from their farms, depending on the season: meat from the animals of the family, lambs, chickens, pigeons, local cheeses, xinomyzithra, kefalotyri, touloumotyri, anthotyro.

Maria Tsantouli remembers:

“My husband’s friends would start from Agkaria, with the local instruments toubaki and tsambouna and by the time they got home to Drios, the table was set…”

These gatherings were a good opportunity for everyone to show their talent… Someone was good at jokes, another at stories, real or fictional, another at jesting or singing and another “would whirl in ballos” (spinning a lot when dancing the ballos). The musicians were paid by the revellers, who danced to the songs they requested.

When the party mood was on the rise, singing and dancing followed, and family relatives or friends played musical instruments as best they could. At home parties, dancing usually started by the host or the best dancer and singing was started by musicians or by anyone with a good voice and a passion for it.

In addition to holiday festivities, houses with large halls in Marpissa, such as those of Paraskevi Tzioti – Lagadiani, Katina Pouliou – Kalamatiani and Mina Anousaki of Kourelas, hosted social gatherings and parties. In the morning of the festive day, which was usually a Saturday or Sunday, the crier would go out and announce the house where the instruments would play. Later, feasts were held at the Agricultural Club.

The greatest party took place at the “dance school” of Marpissa. […] Mrs Vasiliki Tzioti, who was also called Lagkadiani, before the war but also after the war, offered the big hall of her house and on the weekends they held a ball, where beginners (who had not danced before) could learn to dance, accompanied by the sound of the tsambouna and the toubaki. […] Later, Mrs Vassiliki took it one step further and invited bands, Kointemis and Vitzilaios, as well as the band of Angelides. When Antonis Mileos from Marmara (Kointemis) played the “armenaki”… it was breathtaking. (Ragousi-Kontogiorgou, 2004, p. 408)

Sources

Archives of the Association “Routes in Marpissa”.

Ragousi-Kontogiorgou, K. (2004). Πάρος και Αντίπαρος: το εικονοστάσι της ψυχής μου (Paros and Antiparos: the icon stand of my soul). Paros: Anthemion.

Stellas, Z. (2004). της ΠάΡΟΣ, ζουγραφιές ατσούμπαλες, ΑΗΘΕΙέΣ και άλλα λαογραφικά και γλωσσικά. (Paros, unshapely paintings: Novelties and other elements of folklore and language) Athens: n.p.

Special thanks to Katina Alipranti-Anastasiadou, Nikitas Aliprantis, Nikolas Tsigonias (Boutsis), Sofia Kefala, Margarita Malamateniou, Kaiti Pastra, Fanouris Petropoulos, Maria Tsantouli, Betty Tsantouli – Stella, Zafeira Frantzi – Vitzilaios for the information and their valuable assistance.